Protecting Ports from Flooding and Sea Level Rise

Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation at U.S. Ports, an EESI issue brief that examines the topic from a variety of angles. We’re highlighting the section on flooding here.

Climate impacts are increasingly affecting port operations. As a result, ports must consider their near-term and long-term climate change vulnerabilities when planning for the future. In many cases, infrastructure will be needed to protect ports from flooding and sea level rise.

Gray Infrastructure for Shoreline and Flood Protection

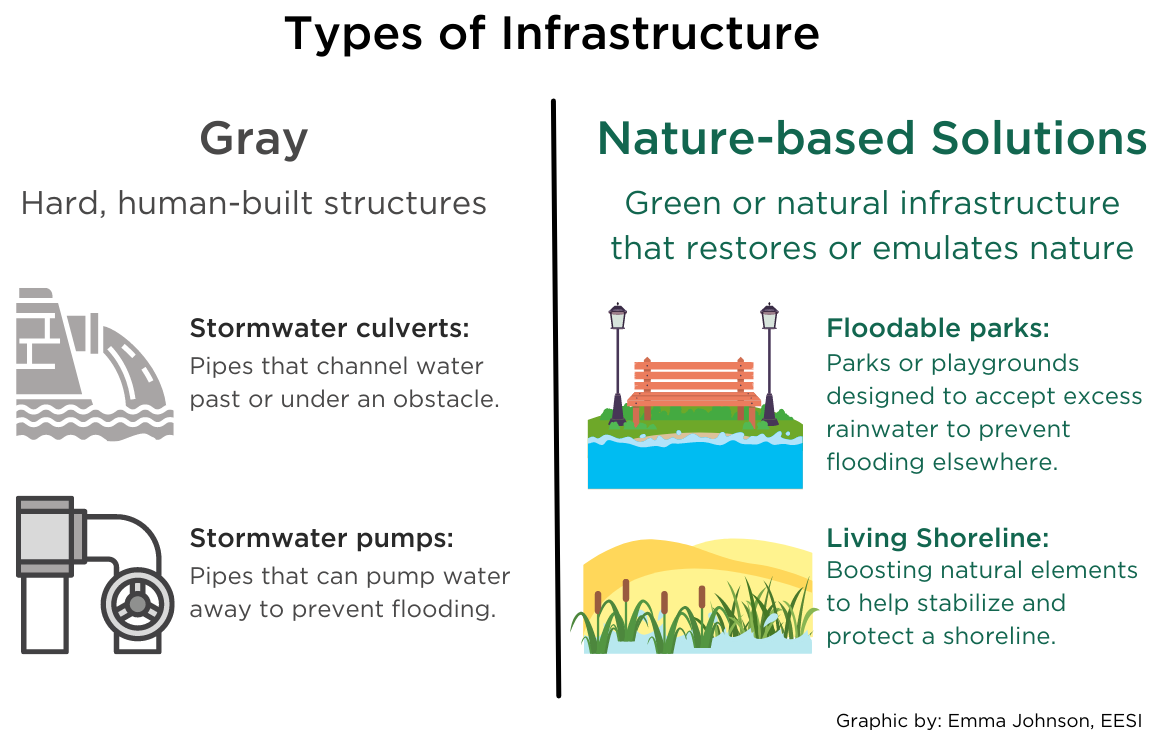

Shoreline and flood protection come in two forms, gray infrastructure and nature-based solutions. Gray infrastructure is hard, human-constructed infrastructure whereas nature-based solutions include green and natural infrastructure (as discussed in the section below). Many ports employ gray infrastructure—including wave attenuators such as bulkheads and seawalls—to combat sea level rise, flooding, and increased wave action from extreme weather. In its Climate Adaptation and Coastal Resiliency Plan, the Port of Long Beach identifies several gray infrastructure-focused climate adaptation strategies, including the installation of concrete barrier walls to protect against flooding.

Some hard structures can be built using specialized building materials that improve habitat. In 2021, the Port of San Diego launched a three-year pilot project with ECOncrete, an eco-engineering company, to develop shoreline and erosion infrastructure that will provide habitat value. The port hopes ECOncrete’s environmentally sensitive concrete solutions will lead to shoreline stabilization, coastal flooding prevention, and improve habitats.

Nature-based Infrastructure for Shoreline and Flood Protection

Research has shown that nature-based infrastructure—such as wetlands, reefs, living shorelines (an approach for addressing shoreline erosion that uses natural materials like plants, rocks, and sand), coastal dunes, and mangroves—can be just as effective, and often more effective, than gray infrastructure at protecting ports from climate impacts. Nature-based solutions also provide the additional benefits of mitigating climate change, supporting plant and animal biodiversity, and improving water quality while also avoiding the use of carbon-intensive materials such as concrete, cement, and steel.

The Port of Miami restored 40 acres of mangroves at Oleta River State Park, planted trees at the port, and relocated coral to a designated Coral Habitat Area on port property, all of which increase the port’s climate resilience and support wildlife habitat. The Port of San Diego’s 2019 Sea Level Rise Vulnerability Assessment and Coastal Resiliency Report looked at living shorelines and living breakwaters as approaches to protect shorelines from erosion and reduce wave action. Beyond breakwaters, green and natural infrastructure like floodable parks, bioswales, and rain gardens can prevent flood damage to buildings during extreme weather while also providing habitat for plants and animals. The Port of Portland, for example, has installed rain gardens and vegetated swales as green infrastructure for managing stormwater.

Stormwater

Effective stormwater management is crucial for protecting ports from more frequent and severe storms and extreme weather caused by climate change. Stormwater runoff can pick up pollutants on paved surfaces at ports and impact water quality by depositing them in the ocean or other bodies of water without treatment. Using a Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) grant, the Port of Baltimore installed a concrete stormwater management system to hold large amounts of water during extreme rain events. The TIGER grant also enabled the elevation of some of the port’s important assets, improving its resilience to sea level rise.

Other ports have used nature-based solutions for treating stormwater. The Port of Seattle uses oyster shells in stormwater catchment basins to increase the amount of dissolved calcium and magnesium in water and remove copper. The Georgia Port Authority created nine acres of wetlands, which treat 100 million gallons of stormwater every year and provide habitat for plants and animals. Reducing port-related water pollutants can also improve surrounding aquatic ecosystems. The Port of San Diego found that hull paint released copper into waterways, which affected the port’s marine ecosystem. Through repainting and cleaning programs, the port reduced copper in the water by 45 percent.

Read the full issue brief on the EESI website. EESI work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License.